SIST EN 17463:2021

(Main)Valuation of Energy Related Investments (VALERI)

Valuation of Energy Related Investments (VALERI)

This document specifies requirements for a valuation of energy related investments (VALERI). It provides a description on how to gather, calculate, evaluate and document information in order to create solid business cases based on Net Present Value calculations for ERIs. The standard is applicable for the valuation of any kind of energy related investment.

The document focusses mainly on the valuation and documentation of the economic impacts of ERIs. However, non-economic effects (e.g. noise reduction) that can occur through undertaking an investment are also considered. Thus, qualitative effects (e.g. impact on the environment) - even if they are non-monetisable - are taken into consideration.

Bewertung von energiebezogenen Investitionen (VALERI)

Dieses Dokument legt Anforderungen für eine Bewertung von energiebezogenen Investitionen (ValERI) fest. Es enthält eine Beschreibung, wie Informationen gesammelt, berechnet, ausgewertet und dokumentiert werden, um solide Geschäftsfälle auf der Grundlage von Kapitalwertberechnungen für ERI zu erstellen. Die Norm gilt für die Bewertung von energiebezogenen Investitionen jeglicher Art.

Das Dokument befasst sich hauptsächlich mit der Bewertung und Dokumentation der wirtschaftlichen Auswirkungen von ERI. Es werden jedoch auch nichtwirtschaftliche Effekte (z. B. Lärmminderung) berücksichtigt, die durch eine Investition entstehen können. Somit werden qualitative Wirkungen (z. B. Auswirkungen auf die Umwelt) – auch wenn sie finanziell nicht bewertbar sind – berücksichtigt.

Évaluation des investissements liés à l'énergie (VALERI)

Dieses Dokument legt Anforderungen für eine Bewertung von energiebezogenen Investitionen (en: Valuation of Energy Related Investments, VALERI) fest. Es enthält eine Beschreibung, wie Informationen gesammelt, berechnet, ausgewertet und dokumentiert werden, um solide Business Cases auf der Grundlage von Kapitalwertberechnungen für ERI zu erstellen. Die Norm gilt für die Bewertung von energiebezogenen Investitionen jeglicher Art.

Das Dokument befasst sich hauptsächlich mit der Bewertung und Dokumentation der wirtschaftlichen Auswirkungen von ERI. Es berücksichtigt jedoch auch nichtwirtschaftliche Effekte (z. B. Lärmminderung), die durch eine Investition entstehen können. Somit erfasst das Dokument auch qualitative Wirkungen (z. B. Auswirkungen auf die Umwelt) – auch wenn sie finanziell nicht bewertbar sind.

Vrednotenje investicij v zvezi z energijo (VALERI)

General Information

- Status

- Withdrawn

- Public Enquiry End Date

- 31-Mar-2020

- Publication Date

- 14-Oct-2021

- Withdrawal Date

- 07-Jan-2026

- Technical Committee

- I11 - Imaginarni 11

- Current Stage

- 9900 - Withdrawal (Adopted Project)

- Start Date

- 08-Jan-2026

- Due Date

- 31-Jan-2026

- Completion Date

- 08-Jan-2026

Relations

- Effective Date

- 01-Feb-2026

- Effective Date

- 28-Jan-2026

Get Certified

Connect with accredited certification bodies for this standard

DNV

DNV is an independent assurance and risk management provider.

Lloyd's Register

Lloyd's Register is a global professional services organisation specialising in engineering and technology.

BSI Group

BSI (British Standards Institution) is the business standards company that helps organizations make excellence a habit.

Sponsored listings

Frequently Asked Questions

SIST EN 17463:2021 is a standard published by the Slovenian Institute for Standardization (SIST). Its full title is "Valuation of Energy Related Investments (VALERI)". This standard covers: This document specifies requirements for a valuation of energy related investments (VALERI). It provides a description on how to gather, calculate, evaluate and document information in order to create solid business cases based on Net Present Value calculations for ERIs. The standard is applicable for the valuation of any kind of energy related investment. The document focusses mainly on the valuation and documentation of the economic impacts of ERIs. However, non-economic effects (e.g. noise reduction) that can occur through undertaking an investment are also considered. Thus, qualitative effects (e.g. impact on the environment) - even if they are non-monetisable - are taken into consideration.

This document specifies requirements for a valuation of energy related investments (VALERI). It provides a description on how to gather, calculate, evaluate and document information in order to create solid business cases based on Net Present Value calculations for ERIs. The standard is applicable for the valuation of any kind of energy related investment. The document focusses mainly on the valuation and documentation of the economic impacts of ERIs. However, non-economic effects (e.g. noise reduction) that can occur through undertaking an investment are also considered. Thus, qualitative effects (e.g. impact on the environment) - even if they are non-monetisable - are taken into consideration.

SIST EN 17463:2021 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 03.100.01 - Company organization and management in general; 27.015 - Energy efficiency. Energy conservation in general. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

SIST EN 17463:2021 has the following relationships with other standards: It is inter standard links to SIST EN 17463:2021+A1:2026, SIST EN ISO 22598:2020. Understanding these relationships helps ensure you are using the most current and applicable version of the standard.

SIST EN 17463:2021 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

SLOVENSKI STANDARD

01-december-2021

Vrednotenje investicij v zvezi z energijo (VALERI)

Valuation of Energy Related Investments (VALERI)

Bewertung von energiebezogenen Investitionen (VALERI)

Évaluation des investissements liés à l'énergie (VALERI)

Ta slovenski standard je istoveten z: EN 17463:2021

ICS:

03.100.01 Organizacija in vodenje Company organization and

podjetja na splošno management in general

27.015 Energijska učinkovitost. Energy efficiency. Energy

Ohranjanje energije na conservation in general

splošno

2003-01.Slovenski inštitut za standardizacijo. Razmnoževanje celote ali delov tega standarda ni dovoljeno.

EUROPEAN STANDARD

EN 17463

NORME EUROPÉENNE

EUROPÄISCHE NORM

October 2021

ICS 03.100.01; 27.015

English version

Valuation of Energy Related Investments (VALERI)

Évaluation des investissements liés à l'énergie Bewertung von energiebezogenen Investitionen

(VALERI) (VALERI)

This European Standard was approved by CEN on 2 August 2021.

CEN and CENELEC members are bound to comply with the CEN/CENELEC Internal Regulations which stipulate the conditions for

giving this European Standard the status of a national standard without any alteration. Up-to-date lists and bibliographical

references concerning such national standards may be obtained on application to the CEN-CENELEC Management Centre or to

any CEN and CENELEC member.

This European Standard exists in three official versions (English, French, German). A version in any other language made by

translation under the responsibility of a CEN and CENELEC member into its own language and notified to the CEN-CENELEC

Management Centre has the same status as the official versions.

CEN and CENELEC members are the national standards bodies and national electrotechnical committees of Austria, Belgium,

Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy,

Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Republic of North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia,

Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and United Kingdom.

CEN-CENELEC Management Centre:

Rue de la Science 23, B-1040 Brussels

© 2021 CEN/CENELEC All rights of exploitation in any form and by any means Ref. No. EN 17463:2021 E

reserved worldwide for CEN national Members and for

CENELEC Members.

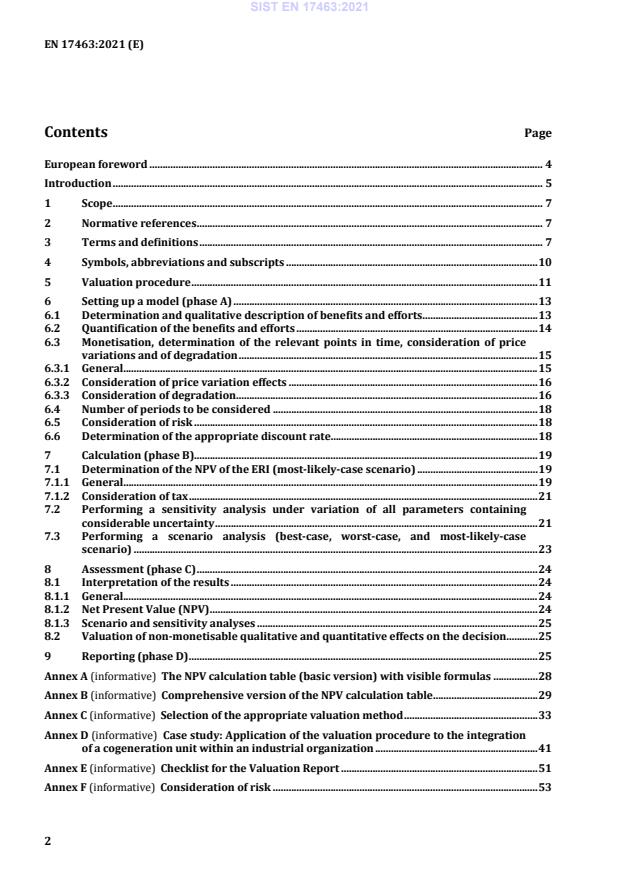

Contents Page

European foreword . 4

Introduction . 5

1 Scope . 7

2 Normative references . 7

3 Terms and definitions . 7

4 Symbols, abbreviations and subscripts . 10

5 Valuation procedure . 11

6 Setting up a model (phase A) . 13

6.1 Determination and qualitative description of benefits and efforts . 13

6.2 Quantification of the benefits and efforts . 14

6.3 Monetisation, determination of the relevant points in time, consideration of price

variations and of degradation . 15

6.3.1 General. 15

6.3.2 Consideration of price variation effects . 16

6.3.3 Consideration of degradation . 16

6.4 Number of periods to be considered . 18

6.5 Consideration of risk . 18

6.6 Determination of the appropriate discount rate. 18

7 Calculation (phase B). 19

7.1 Determination of the NPV of the ERI (most-likely-case scenario) . 19

7.1.1 General. 19

7.1.2 Consideration of tax . 21

7.2 Performing a sensitivity analysis under variation of all parameters containing

considerable uncertainty . 21

7.3 Performing a scenario analysis (best-case, worst-case, and most-likely-case

scenario) . 23

8 Assessment (phase C) . 24

8.1 Interpretation of the results . 24

8.1.1 General. 24

8.1.2 Net Present Value (NPV) . 24

8.1.3 Scenario and sensitivity analyses . 25

8.2 Valuation of non-monetisable qualitative and quantitative effects on the decision . 25

9 Reporting (phase D) . 25

Annex A (informative) The NPV calculation table (basic version) with visible formulas . 28

Annex B (informative) Comprehensive version of the NPV calculation table. 29

Annex C (informative) Selection of the appropriate valuation method . 33

Annex D (informative) Case study: Application of the valuation procedure to the integration

of a cogeneration unit within an industrial organization . 41

Annex E (informative) Checklist for the Valuation Report . 51

Annex F (informative) Consideration of risk . 53

Annex G (informative) Consideration of price variation . 56

Bibliography . 57

European foreword

This document (EN 17463:2021) has been prepared by Technical Committee CEN/CLC/JTC 14 “Energy

efficiency and energy management in the framework of energy transition”, the secretariat of which is

held by UNI.

This European Standard shall be given the status of a national standard, either by publication of an

identical text or by endorsement, at the latest by April 2022, and conflicting national standards shall be

withdrawn at the latest by April 2022.

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. CEN-CENELEC shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

Any feedback and questions on this document should be directed to the users’ national standards

body/national committee. A complete listing of these bodies can be found on the CEN and CENELEC

websites.

According to the CEN-CENELEC Internal Regulations, the national standards organisations of the

following countries are bound to implement this European Standard: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria,

Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland,

Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Republic of

North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and the

United Kingdom.

Introduction

In order to reach the energy related targets of the EU and its member states, energy related investments

(ERIs) have to increase. A possible lack of investments could not only result from a lack of the available

capital, but also from a lack of reliable financial evaluations of the benefits of ERIs.

Different investment ideas often compete for the available money within organisations. Therefore,

enhancement of the financeability of ERIs can be achieved by showing the full economical value that

they are able to generate. When this is done properly, priorities for budgets of ERIs should rise

automatically and thus more investments will be undertaken.

The state of the art of today’s energy related project valuation in practise reveals that in order to help

the user to undertake a firm and correct valuation it is necessary to avoid:

— incorrect results which are caused by neglecting relevant parameters and cash flows;

— unclear calculation models which are difficult to understand;

— models containing errors or models that are incomplete;

— use of calculated costs instead of cash flows;

— time value of money not being considered;

— discount rate being used in an unreflected manner;

— risks not being properly considered;

— missing sensitivity and scenario analyses;

— missing traceability;

— missing interpretation of results;

— price variation rates (very important for energy project valuation) not being appropriately

considered.

The objectives of this document are:

— to help proposers of energy related investments (ERIs) to evaluate their ideas economically and

qualitatively in a uniform, transparent and understandable way by generating all material

information that is relevant for a decision,

— to generate comparable results (for this it is important to ensure that the estimation of the cash

flows is done in a comparable way by using correct price variations, the use of marginal prices for

all cash flows etc.),

— to help the valuator to generate valuation results that can be easily understood by those who decide

upon them,

— to help the decision maker and possible financial institutions who decide on the basis of the

valuation results and expect the results to be correct and complete but also easy to understand,

retraceable and explicit (material),

— to complement other standards or protocols that focus on the technical determination of energy

savings and

— to help those persons that decide upon ERIs.

In order to accomplish these objectives this document offers a valuation procedure, a calculation

methodology (just one), and a documentation structure that covers the following features:

— application of one calculation method only;

— correct and complete results (Net Present Value considering among other things also, all relevant

cash flows and their price variation rates over the whole project lifetime);

— unequivocal (one indicator at the end which can be directly used for decision-making);

— uniform (a standard);

— easy to use (table based, one uniform calculation table);

— retraceable and easy to reproduce (calculations are transparent and the assumptions made are

explained);

— as simple as possible;

— flexible (the user can adjust parameters and can customise the calculation table);

— undertaking of sensitivity and scenario analyses;

— the standard contains templates for reporting the calculation results and all additional qualitative

effects.

Transparent calculations including retraceable assumptions that show the full value of ERIs will help

organisations as well as households to identify the added value resulting from such ERIs. The proposed

methodology could also be used in energy reviews or audits (using EN 16247-1), when prioritising

energy performance improvement potentials.

An easy to use and standardized procedure would be helpful as energy management teams might not

always include personnel that are equipped to translate technical ideas into conclusive economical

results in order to ensure a solid basis for decision-making.

This document relates to standards regarding energy management and energy savings in general. It

proposes the use of “Net Present Value” (NPV) calculations and its result as a basis for decision-making

(see Annex C).

1 Scope

This document specifies requirements for a valuation of energy related investments (VALERI). It

provides a description on how to gather, calculate, evaluate and document information in order to

create solid business cases based on Net Present Value calculations for ERIs. The standard is applicable

for the valuation of any kind of energy related investment.

The document focusses mainly on the valuation and documentation of the economic impacts of ERIs.

However, non-economic effects (e.g. noise reduction) that can occur through undertaking an investment

are also considered. Thus, qualitative effects (e.g. impact on the environment) – even if they are non-

monetisable – are taken into consideration.

2 Normative references

There are no normative references in this document.

3 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the following terms and definitions apply.

ISO and IEC maintain terminological databases for use in standardization at the following addresses:

— ISO Online browsing platform: available at https://www.iso.org/obp

— IEC Electropedia: available at https://www.electropedia.org/

3.1

adjustment parameter

quantifiable parameter affecting the results of the valuation process

EXAMPLE energy savings (kWh), discount rate, project lifetime, energy price variation rates etc.

3.2

degradation

decrease in the performance characteristics or service life of a product

Note 1 to entry: The degradation rate is measured as performance decline per year (e.g. 1 %/a).

Note 2 to entry: For the purpose of this document deterioration (decline in the performance of an energy

performance improvement action) is included in the concept of degradation.

[SOURCE: EN 60194:2007-03, modified — Note 1 and Note 2 to entry added]

3.3

benefit

positive effect resulting from an investment

Note 1 to entry: A benefit can have a qualitative, quantitative, financial or fiscal nature.

Note 2 to entry: A benefit can be a direct or indirect effect.

3.4

cash flow

movement of money

EXAMPLE Initial payment of an investment.

Note 1 to entry: Depreciation is not a cash flow.

Note 2 to entry: In this document cash flow is also referred to as payment (P).

Note 3 to entry: Energy savings are considered as cash flows into a business or project as they reduce the

payments for energy consumption.

3.5

discount factor q

multiplier (1+r) of a cash flow to calculate the Present Value (PV) depending on the discount rate (r)

and the period (t)

t t

Note 1 to entry: For each period (t) the cumulated discount factor is calculated with (1+r) or q .

3.6

discount rate r

interest rate that reflects the time value of money

Note 1 to entry: Abbreviated by r (r for required rate of return).

Note 2 to entry: The risk can also be taken into account when setting the value of the discount rate.

3.7

effort

negative effect resulting from an investment

Note 1 to entry: An effort can have a qualitative, quantitative, financial or fiscal nature.

Note 2 to entry: The negative effects occur in a direct or indirect way.

3.8

energy related investment (ERI)

any kind of investment in which energy consumption or energy generation plays a role irrespective

whether it is an energy performance improvement action or an energy supply system project

3.9

internal rate of return (IRR)

discount rate at which the Net Present Value (NPV) of all cash flows of a project equals zero for the

lifetime of the project

3.10

investment risk

volatility of the return of an investment, particularly the likelihood of occurrence of losses relative to

the expected return on any particular investment

Note 1 to entry: Investment risks can derive from credit risk, construction risks, operational and maintenance

risks, performance risks etc.

3.11

lifetime of an investment

period during which the investment causes cash flows

Note 1 to entry: Guidance for the lifetime of energy related investments with regard to buildings can be found in

EN 15459-1.

3.12

monetisation

transformation of benefits and efforts into cash flows

Note 1 to entry: This is usually done by multiplying the quantified benefits and efforts with the specific monetary

value per unit.

3.13

Net Present Value

(NPV)

sum of discounted cash flows over the whole lifetime of an investment

3.14

non-energy effect

effect that results from an ERI but is not directly related to the energy consumption or generation

EXAMPLE motivation of employees, increased production capacity, less noise, better working conditions etc.

3.15

payback period

time required to recover the payments out of an investment

3.16

risk premium

compensation for investors accounting for the given risk compared to that of a risk-free asset

Note 1 to entry: Risk premium can be included in the interest rate or defined as an additional cash flow.

3.17

scenario analysis

procedure to calculate extreme but still realistic results

3.18

sensitivity analysis

procedure to assess the impact of changes of adjustment parameter settings on the NPV

3.19

valuation of energy related investments

(VALERI)

procedure of assessing and reporting financial and non-financial effects of an ERI in order to lay a

foundation for decision-making

4 Symbols, abbreviations and subscripts

For the purposes of this document, the specific symbols, abbreviations and subscripts listed in Table 1

apply.

Table 1 — Symbols, abbreviations and subscripts

Symbol Name of quantity Unit

CAPEX Capital Expenditure €

C Debt capital €

debt

C Equity capital €

eq

C Total investment capital €

invest

CHP Combined Heat and Power system

ded Deduction to account for risk in period t (= ∑P ⋅ f ) €

risk, t t ded_risk

degrad Annual degradation

DPB or DPP Discounted Payback Period years

epr Annual price variation energy

E Annual energy savings for energy carrier “A” without considering kWh/year

savings, A

degradation

f Risk deduction factor (= p ⋅ R )

ded_risk loss loss

IRR Internal Rate of Return

it Income tax rate

NPV Net Present Value €

OPEX Operational Expenditure €

P Payment (payment in or payment out) €

p Probability of the occurrence of net return loss

loss

pr Annual price variation not energy

PV Present Value

q Discounting factor (= 1+r)

r Interest rate for debt capital

debt

bt

r Interest rate for debt capital (before taxes)

debt

at bt

r Interest rate for debt capital after taxes (= r ⋅ [1–it])

debt debt

r Interest rate for equity capital

eq

at at

r Expected return on equity after taxes (= r ⋅ [1–it])

eq eq

bt

r Expected return on equity before taxes (= r + β ⋅ [r – r ])

eq f m f

r Interest rate for a risk-free investment

f

R Risk expressed in a quantified return loss

loss

r Nominal discount rate

nominal

Symbol Name of quantity Unit

r Real discount rate

real

r discount rate in period t

t

Sdebt Share of debt capital (= Cdebt/Cinvest)

S Share of equity capital (= C /C )

eq eq invest

SpecPrice Specific energy price (energy carrier A) in period t €/kWh

energy_A, t

SPP or SPB Simple Payback Period years

t period year

T Lifetime of the investment years

Ttax Depreciation period (only relevant if taxes are considered) years

VAT Value Added Tax

WACC Weighted Average Cost of Capital after taxes in first year

at

at at

(= S ⋅ r + S ⋅ r )

eq eq debt debt

WACC Weighted Average Cost of Capital before taxes in first year

bt

bt bt

(= S ⋅ r + S ⋅ r )

eq eq debt debt

5 Valuation procedure

For the valuation of an ERI the organization shall (as shown in Figure 1) complete the following tasks:

A. Setting up the model:

1. determine all benefits and efforts that result from the given ERI (including all relevant energy

flows);

2a. quantify the benefits and efforts of the potential investment;

2b. describe in a qualitative manner all those effects that can’t be quantified;

3a. monetise the benefits and efforts to payments out and payments in (the relevant cash flows) taking

into account the expected price variations for each cash flow, and estimated degradation;

3b. specify non-monetisable effects;

4. determine the number of periods that should be considered (regularly the lifetime of an

investment) and specify the points in time when the cash flows occur;

5. estimate all relevant risk factors, as appropriate;

6. determine the appropriate discount rate for discounting the cash flows;

B. Calculation:

7. calculate the Net Present Value of the ERI using the most-likely parameter settings, which will

result in the most-likely-case scenario;

8. perform a sensitivity analysis under variation of all adjustment parameters that are liable to

uncertainty, as appropriate;

9. perform a scenario analysis including at a minimum a worst-case, and best-case scenario;

C. Assessment:

10. interpret the quantitative and the qualitative results;

D. Reporting:

11. present the calculation and its results in a transparent and retraceable manner.

Figure 1 — Valuation procedure

For explanation purposes the valuation procedure is outlined by using an example for an ERI (here:

exchange pumps for a cooling system).

6 Setting up a model (phase A)

6.1 Determination and qualitative description of benefits and efforts

Initially, all benefits and efforts that result from an ERI shall be described as qualitative data. This

process requires thinking beyond the obvious financial effects in order to account for all benefits and

efforts which might be relevant for the investment decision.

The organization shall divide “benefits and efforts” into the sub-categories

— “energy flow effects” (expressed as energy and financial effects),

— “additional financial effects” (that go beyond the energy flow effects), and

— “miscellaneous effects”, if applicable,

as shown in Table 2.

Visualization of energy flow effects might improve the overall understanding. This could be done by

setting up an energy flow chart (see example in Annex D).

“Additional financial effects” and “miscellaneous effects” are considered as “non-energy effects” which

can have a strong influence on the profitability of an investment (e.g. subsidies, increase in productivity,

marketing effects etc.) and should therefore be included in the valuation.

Qualitative effects such as noise reduction, cleaner air, less pollution, less GHG emission etc. shall be

checked. All effects shall be listed and will be included later in the valuation report to show all financial

and other impacts of the investment.

When determining the benefits and efforts of the ERI indirect effects can occur that result from the

investment, including:

— cost reduction resulting from lower CO taxes and GHG emission allowances,

— other tax related incentives connected with energy related investments.

EXAMPLE An energy performance improvement action leads to a reduction in electricity use of 150 000 kWh

per year. Assuming an individual CO factor for electricity of 486 g/kWh the action leads to a CO reduction of

2 2

72,9 tons per year. Should the CO2-tax amount to 80 € per ton this would lead to an additional financial benefit of

5 832 € per year.

At this stage benefits and efforts are listed, but they are not quantified or monetised. At the end of this

step the results could look like Table 2.

Table 2 — Benefits and efforts of the given example

Example: replacement of pumps in a cooling

Effects of the ERI

system in order to increase the energy efficiency

Initial investment for new pumps

additional financial effects

Efforts Designing a new pump system

miscellaneous effects Production losses during set up

energy flow effects Annual energy savings (electricity)

Less maintenance and repair costs

additional financial effects Scrap value of old pumps

Benefits Potential incentives (e.g. tax reductions)

Noise reduction

miscellaneous effects Enhancement of production reliability

New pumping system takes up less space

Sometimes energy performance improvement actions require additional energy flows in order to

generate a net energy efficiency advantage (e.g. CHP systems, see example in Annex D). These additional

energy flows shall also be considered at this stage (in section “efforts”).

6.2 Quantification of the benefits and efforts

In the second step, all effects that were gathered in step 1 shall be quantified, if possible.

The estimation of the

— expected energy savings through the energy performance improvement action or

— energy generated through the usage of new or improved energy supply systems

shall be based on relevant, reliable, traceable and transparent technical calculations. These calculations

can be conducted by the organization or an external service provider with adequate competences in

energy matters.

Calculations should also take into account information on possible degradation over time (see 6.3).

NOTE Guidance for calculations of energy savings can be found in e.g. EN 16212, ISO 17741 or, ISO 50046.

The methodology for such calculations however is not part of this standard.

Table 3 shows the data for the given example in which the quantified values reveal the most-likely-case.

Table 3 — Quantification of benefits and efforts

Effects of the ERI Quantity

Initial investment for new pumps 5 pumps

additional

financial effects

Designing new pump system 100 h

Efforts

miscellaneous 15 h during the exchange of

Production losses during set up

effects the pumps

energy flow

Annual energy saving (electricity) 150 000 kWh/a

effects

Less maintenance and repair costs 5 h less every two years

additional

financial effects

Scrap value of old pumps 5 pumps

Benefits

Noise reduction reduction from 90 ⟶ 65 dB

miscellaneous Enhancement of production reliability not quantifiable

effects

New pumping system takes up less

10 m of space saving

space

Effects which cannot be quantified could also be relevant for the decision. Therefore, they shall be

described, weighted regarding their relevance and - if relevant for the decision - be assessed (see 8.1)

and considered in the valuation report (see Clause 9).

6.3 Monetisation, determination of the relevant points in time, consideration of price

variations and of degradation

6.3.1 General

Quantified benefits and efforts shall be transferred into cash flows, if possible. In order to achieve this,

the quantities are multiplied by the specific value for each unit whereas the multipliers reveal the most-

likely-case.

For each cash flow the organization shall determine:

— whether it is a regular or a single cash flow and when the cash flow will occur (point in time),

— what the expected price variation for each cash flow-series will be over the whole lifetime of the

investment, and

— the effect of the degradation.

Price variations can vary for different goods and services; therefore, differentiated price variation rates

shall be used, as appropriate. All assumptions for price variations shall be mentioned and explained in

the valuation report. The applied degradation rate shall be mentioned in the valuation report as well as

the source of information.

Quantifiable effects that cannot be monetised could also be relevant for the decision. Therefore, they

shall be described, weighted regarding their relevance and - if relevant for the decision - be assessed

(see 8.1) and considered in the valuation report (see 9).

6.3.2 Consideration of price variation effects

In general, there are two options to consider price variation effects within an NPV calculation:

— One option is to calculate the NPV with inflation-adjusted cash flows (i.e. after removing the effects

of inflation), so calculating with “real” values.

— Another option is to use nominal values (i.e. revealing the price variation of the cash flows over

time).

For valuations of energy related investments, only nominal values (not real values) as cash flow streams

shall be used. Inflation adjustment should be avoided as long as models deal with different price

variation rates such as energy investments (see explanation in Annex G).

For the given example the price variation rates were set at 3 % per year for energy and 2 % per year for

maintenance (see Table 4).

The assumptions for the price variation rates shall be described in the valuation report.

6.3.3 Consideration of degradation

Degradation is the decline of performance over time, differentiated in either

— an ongoing reduction of power supplied (energy supply systems) or

— a change in the performance of energy performance improvement actions after implementation,

leading to a decrease in annual energy savings (also referred to as “deterioration”). It could be

related to system characteristics (e.g. by fouling of the heat exchanger in the boiler) or to

behavioural change of people reverting back to their old habits or behaviour on energy use or even

consuming more energy as a reaction to reduced specific energy costs (rebound).

The degradation rate is measured as performance decline per year (e.g. 1 %/a).

For the given example the degradation is set to 0 %. The results for the given example are shown in

Table 4.

Table 4 — Overview of all effects, their characteristics and the time allocation of cash flows

Value per

To be

Monetisation unit Point in Price

Effects of the ERI Quantity Amount Degradation included in

possible? (specific time variation

final report?

costs)

Initial investment for

5 pumps yes 10 000 € 50 000 €/a year 0 – n.a.

new pumps

Designing new pump

100 hours yes 50 €/h 5 000 €/a year 0 – n.a.

system

15 hours during

Production losses

the exchange of partially 200 €/h 3 000 €/a year 0 – n.a.

during set up

the pumps

Annual energy saving every

150 000 kWh/a yes 0,18 €/kWh 27 000 €/a +3 %/a +0 %/a

(electricity) year

5 h less every two every

Less maintenance yes 50 €/h 250 €/a +2 %/a n.a.

years 2 years

reduction from every

Noise reduction no – – – n.a.

90 ⟶ 65 dB year

Scrap value of old

5 pumps yes 300 € 1 500 €/a year 0 – n.a.

pumps

New pumping system every

10 m no – – – n.a.

takes up less space year

NOTE The unit €/a is equal to €/year.

Benefits Efforts

6.4 Number of periods to be considered

The organization shall estimate the planning horizon T taking into account the total length of time in

which the investment generates cash flows (project lifetime).

The planning horizon T shall be estimated with care as differences between expected and real project

lifetime can result in considerable inaccuracies and - as a consequence of that - in faulty decisions.

NOTE The following questions can help to determine the lifetime of an investment:

— How long does the investment generate effects?

— How long can monetisable benefits and efforts be expected through the investment?

— When can reconstruction, repowering, dismantling, major overhaul, disposal etc. and the relevant

associated cash flows be expected?

If different investment projects shall be compared and ranked by means of their calculated NPV, it is not

economically relevant if they differ in their lifetimes. No additional calculations are necessary to make

the results comparable as long as the discount rate has been set appropriately (see 6.6).

All assumptions regarding the lifetime settings shall be mentioned and explained in the valuation

report.

The planning horizon for the given example is set to 15 years.

6.5 Consideration of risk

Investment risks have an impact on the NPV. They can be considered as the volatility of the returns of

an investment. Two investment options with the same cash flow series and the same adjustment

parameter settings, but with different risks regarding their returns, would have different values for the

investor.

Therefore, risks should be considered in NPV calculations as a risk premium which can be included in

the interest rate or can be defined as an additional cash flow.

Besides the inclusion of a risk premium, a risk assessment can be complemented by (a.) sensitivity and

(b.) scenario analyses, whereas the sensitivity analysis reveals those parameters with the strongest

effect on the NPV and the scenario analysis accounts for the variation band of the NPV results („worst-

and best-case scenario“, see 7.3 and 8.1).

The organization should state their assumptions and their risk considerations in the valuation report.

Further information on how to incorporate risk assumptions into the valuation can be found in Annex F.

All assumptions regarding risk should be mentioned and explained in the valuation report.

6.6 Determination of the appropriate discount rate

For the valuation of ERIs a discount rate r shall be determined. The discount rate is used to incorporate

the time value of money into the valuation calculation. It shall express the requirement that is expected

from an investment (r for required rate of return).

The determination of the discount rate depends on the way of financing an investment. If the

investment is financed by 100 % equity capital C then the discount rate r shall be set to the internal

eq

rate of return of the risk equal best available alternative .

By using the discount rate it is possible for the organisation to compare the new investment against the return

of normal business practices as this is regularly the given alternative for investment of organisations. In such a

case the discount rate is equal to the return on total assets (ROA).

In contrast, if debt capital is the basis of the investment then the interest rate of the debt shall be used

for the value of r.

In cases where the financing sources of the investment are mixed, the “weighted average cost of capital”

(WACC) can be chosen as r:

C

C

eq

debt

r WACC ⋅+r ⋅ r

eq debt

C C

invest invest

where

r is the interest rate of equity capital;

eq

r is the interest rate of the debt.

debt

The discount rate used shall be mentioned and explained in the valuation report if applicable as well as

the source of the information.

The discount rate for the given example is calculated as 6,96 % as shown in Table 5.

Table 5 — Calculating the discount rate (WACC)

Determination of interest rate Value

Share of equity capital S (= C /C )

eq invest 80 %

eq

Share of debt capital S (= C /C )

debt invest 20 %

debt

r = interest rate of equity capital

7,2 %

eq

r = interest rate of the debt capital

6,0 %

debt

r = Weighted average cost of capital WACC (= S ⋅ r + S ⋅ r ) 6,96 %

eq eq debt debt

NOTE 1 The final example value results from the calculation: “80 % ⋅ 7,2 % + 20 % ⋅ 6 % = 6,96 %”.

NOTE 2 When determining the share of debt capital, organisations can consider the calculation of the debt

service coverage ratios (DSCRs) as an indicator for lenders.

NOTE 3 Guidance for the lifetime of energy related investments with regard to buildings can be found in

EN 15459-1.

The discount rate is typically one of the most influential adjustment parameters of NPV calculations.

Therefore, its setting shall be undertaken with caution and be explained in the valuation report.

It is recommended to involve the appropriate person of the organization in the determination of the

WACC.

7 Calculation (phase B)

7.1 Determination of the NPV of the ERI (most-likely-case scenario)

7.1.1 General

In order to determine the added value of the ERI the NPV shall be calculated. All monetisable benefits

and efforts (cash flows) shall be inserted into a calculation table for each period taking into account the

= =

predetermined price variation rates. Table 6 shows such a calculation table, and the results for the

given example .

Table 6 — Calculation of the NPV for the given example (most-likely-case)

End of operating period t 0 1 2 … 15

Discount rate r 6,96 %

Annual price variation energy

3 %

epr

Annual price variation not

2 %

energy pr

Actual specific energy price 0,18 €/kWh

Number of periods to be

15 years

considered

Payments out Base values

Initial investment 60 000 € -60 000 € …

Design costs 5 000 € -5 000 € …

Production losses during set

3 000 € -3 000 € …

up

Payments in Base values

Annual energy savings 150 000 kWh/a 27 810 € 28 644 € … 42 065 €

Less maintenance 250 € 255 € 260 € … 336 €

Scrap value of old pumps 1 500 € 1 500 € …

Total -66 500 € 27 810 € 28 904 € … 42 065 €

Present values (PV) -66 500 € 26 000 € 25 265 € … 15 332 €

Net Present Value (NPV) 239 603 €

NOTE 1 The NPV of 239 603 € considers a project lifetime of 15 years.

NOTE 2 A period represents a time span of one year. If the ERI for example is implemented in April, a period

represents a time span from April to March until the end of the lifetime of the investment.

The sum of the cash flows for each period shall be discounted in order to calculate the Present Values of

the net cash flows. This discounting procedure can be seen as a normalization of future cash flows to the

value they have today.

The Present Values shall be summed up to a single indicator which is the Net Present Value. The NPV-

formula is as follows:

T

P

PP P

1 2 T t

NPV P+ + +…+

∑

2 Tt

q

q qq

t=0

The formulas used in each cell of table 6 are illustrated in Annex A.

= =

where

q = (1+r) is the discounting factor;

P is payment at the end of period t;

t

r is discount rate (as decimal value).

This procedure allows the comparison of different options regardless of their lifetime as the NPV

incorporates all (monetisable) effects that occur over the whole lifetime of the investment.

7.1.2 Consideration of tax

The organization can consider the inclusion of tax related effects in the calculation. In any case the

organization shall state whether or not taxes are considered. Annex D illustrates how to include tax

payments.

Tax effects regularly result from effects of the investment on the profit of the organization e.g. through

depreciation or other costs like leasing rates etc. So, in order to include taxes in the calculation, these

changes to the profit have to be determined and multiplied by the income tax rate of the company.

Nevertheless, depreciation itself must not be considered as a cash flow in the calculation as its values

are calculated results only (it can only be considered indirectly through tax effects). It is recommended

to involve the appropriate person of the organization in the determination of the applicable tax rate.

7.2 Performing a sensitivity analysis under variation of all parameters containing

considerable uncertainty

In order to gain a deeper understanding of the sensitivity of the NPV on parameter variations the

organization can conduct a sensitivity analysis. The organization should in a first step determine which

parameters contain considerable uncertainty and use these as the basis for the sensitivity analysis.

Regularly those parameters include:

— annual price variation rates;

— amount of energy saved or produced;

— the lifetime of the investment;

— discount rate;

— CAPEX;

— OPEX;

— cash flows regarding the dismantling, disposal or similar at the end of the lifetime.

The sensitivity analysis is performed by varying the input parameters one variation at a time in an

interval chosen by the organization (e.g. from –50 % to +50 % of the most-likely values and assessing

their impact on the NPV). Table 7 illustrates the results of such a sensitivity analysis for the given

example.

Table 7 — Results — Sensitivity Analysis

Settings NPV

Adjustment parameters Slope

@Basic @Value

Value –50 % Basic setting Value +50 % @Value –50 %

setting +50 %

Annual price variation energy 1,5 % 3 % 4,5 % 209 321 € 239 603 € 274 033 € 647 €/Δ%

Annual amount of energy saved or

75 000 kWh/a 150 000 kWh/a 225 000 kWh/a 87 861 € 239 603 € 391 345 € 3 035 €/Δ%

produced

Annual price variation rate for relevant

1,0 % 2,0 % 3,0 % 239 427 € 239 603 € 239 794 € 4 €/Δ%

services and material

Lifetime of the investment T 7,5 15 22,5 97 944 € 239 603 € 308 690 € 2 107 €/Δ%

Discount rate r including risk estimation 3,48 % 6,96 % 10,44 % 327 140 € 239 603 € 178 087 € −1 491 €/Δ%

CAPEX 33 250 € 66 500 € 99 750 € 272 853 € 239 603 € 206 353 € −665 €/Δ%

...

Questions, Comments and Discussion

Ask us and Technical Secretary will try to provide an answer. You can facilitate discussion about the standard in here.

Loading comments...