CEN/CLC/TR 17603-31-10:2021

(Main)Space engineering - Thermal design handbook - Part 10: Phase - Change Capacitor

Space engineering - Thermal design handbook - Part 10: Phase - Change Capacitor

Solid-liquid phase-change materials (PCM) are a favoured approach to spacecraft passive thermal control for incident orbital heat fluxes or when there are wide fluctuations in onboard equipment.

The PCM thermal control system consists of a container which is filled with a substance capable of undergoing a phase-change. When there is an the increase in surface temperature of spacecraft the PCM absorbs the excess heat by melting. If there is a temperature decrease, then the PCM can provide heat by solidifying.

Many types of PCM systems are used in spacecrafts for different types of thermal transfer control.

Characteristics and performance of phase control materials are described in this Part. Existing PCM systems are also described.

The Thermal design handbook is published in 16 Parts

TR 17603-31-01 Part 1

Thermal design handbook – Part 1: View factors

TR 17603-31-01 Part 2

Thermal design handbook – Part 2: Holes, Grooves and Cavities

TR 17603-31-01 Part 3

Thermal design handbook – Part 3: Spacecraft Surface Temperature

TR 17603-31-01 Part 4

Thermal design handbook – Part 4: Conductive Heat Transfer

TR 17603-31-01 Part 5

Thermal design handbook – Part 5: Structural Materials: Metallic and Composite

TR 17603-31-01 Part 6

Thermal design handbook – Part 6: Thermal Control Surfaces

TR 17603-31-01 Part 7

Thermal design handbook – Part 7: Insulations

TR 17603-31-01 Part 8

Thermal design handbook – Part 8: Heat Pipes

TR 17603-31-01 Part 9

Thermal design handbook – Part 9: Radiators

TR 17603-31-01 Part 10

Thermal design handbook – Part 10: Phase – Change Capacitors

TR 17603-31-01 Part 11

Thermal design handbook – Part 11: Electrical Heating

TR 17603-31-01 Part 12

Thermal design handbook – Part 12: Louvers

TR 17603-31-01 Part 13

Thermal design handbook – Part 13: Fluid Loops

TR 17603-31-01 Part 14

Thermal design handbook – Part 14: Cryogenic Cooling

TR 17603-31-01 Part 15

Thermal design handbook – Part 15: Existing Satellites

TR 17603-31-01 Part 16

Thermal design handbook – Part 16: Thermal Protection System

Raumfahrttechnik - Handbuch für thermisches Design - Teil 10: Kondensatoren mit Phasenübergängen

Ingénierie spatiale - Manuel de conception thermique - Partie 10 : Réservoirs de matériaux à changement de phase

Vesoljska tehnika - Priročnik o toplotni zasnovi - 10. del: Kondenzatorji s faznimi prehodi

General Information

- Status

- Published

- Publication Date

- 10-Aug-2021

- Technical Committee

- CEN/CLC/TC 5 - Space

- Drafting Committee

- CEN/CLC/TC 5 - Space

- Current Stage

- 6060 - Definitive text made available (DAV) - Publishing

- Start Date

- 11-Aug-2021

- Due Date

- 14-Jul-2022

- Completion Date

- 11-Aug-2021

Relations

- Effective Date

- 28-Jan-2026

Overview

CEN/CLC/TR 17603-31-10:2021 (Space engineering – Thermal design handbook – Part 10: Phase‑Change Capacitor) is a CEN/CENELEC technical report adopted by SIST that documents the use of solid–liquid phase‑change materials (PCM) as passive thermal control devices for spacecraft. Published in August 2021, this Part of the 16‑part Thermal Design Handbook focuses on PCM capacitor systems (also called phase‑change capacitors or PCM reservoirs) used to absorb and release heat through melting and solidification to manage orbital heat fluxes and large onboard temperature swings.

Key topics covered

The report documents technical subjects relevant to PCM thermal control, including:

- PCM working materials: candidate materials, thermophysical properties (density, specific heat, thermal conductivity, vapor pressure, viscosity), and phenomena such as supercooling, nucleation, bubble formation and the effect of gravity on melting/freezing.

- PCM technology: container and filler design options, materials compatibility and corrosion issues, fillers (honeycomb, fins, etc.), and common packaging approaches illustrated with examples.

- PCM performance: analytical prediction methods, heat transfer relations, and models for melting/freezing behaviour and thermal response.

- Existing systems and test data: documented flight and ground hardware examples (Dornier, IKE, B&K Engineering, Aerojet ElectroSystems, Trans Temp), performance curves, and experimental setups.

- Terms, symbols and references: standardized definitions and notation to support thermal design work.

(These topics reflect the report’s table of contents and figure list; the document includes detailed figures and experimental results for practical design use.)

Practical applications

This technical report is intended to support:

- Spacecraft thermal control design: use PCM capacitors to damp diurnal or transient heat loads, reduce radiator cycling, and extend operational temperature windows.

- Component-level thermal management: thermal buffering for batteries, instruments, gyros and electronics that experience intermittent heating.

- Subsystem selection and trade studies: compare PCMs and packaging options (fillers, containers) for mass, volume and conductance trade‑offs.

- Qualification and testing: guidance on test setups, measurements and performance interpretation for both ground and microgravity environments.

Who should use this standard

- Spacecraft thermal engineers and system engineers

- Satellite and payload designers

- Materials scientists and PCM suppliers

- Thermal test engineers and qualification teams

- Procurement and standards personnel evaluating PCM thermal solutions

Related standards and documents

- This Part is one of 16 in the TR 17603-31 Thermal Design Handbook series, which includes Parts on view factors, heat pipes, radiators, insulations, electrical heating, fluid loops and thermal protection systems - all relevant when integrating PCM thermal control into a spacecraft thermal architecture.

Keywords: phase change materials, PCM, phase‑change capacitor, spacecraft passive thermal control, thermal design handbook, spacecraft thermal management, PCM containers, supercooling, nucleation, microgravity.

Get Certified

Connect with accredited certification bodies for this standard

DEKRA North America

DEKRA certification services in North America.

Eagle Registrations Inc.

American certification body for aerospace and defense.

Element Materials Technology

Materials testing and product certification.

Sponsored listings

Frequently Asked Questions

CEN/CLC/TR 17603-31-10:2021 is a technical report published by the European Committee for Standardization (CEN). Its full title is "Space engineering - Thermal design handbook - Part 10: Phase - Change Capacitor". This standard covers: Solid-liquid phase-change materials (PCM) are a favoured approach to spacecraft passive thermal control for incident orbital heat fluxes or when there are wide fluctuations in onboard equipment. The PCM thermal control system consists of a container which is filled with a substance capable of undergoing a phase-change. When there is an the increase in surface temperature of spacecraft the PCM absorbs the excess heat by melting. If there is a temperature decrease, then the PCM can provide heat by solidifying. Many types of PCM systems are used in spacecrafts for different types of thermal transfer control. Characteristics and performance of phase control materials are described in this Part. Existing PCM systems are also described. The Thermal design handbook is published in 16 Parts TR 17603-31-01 Part 1 Thermal design handbook – Part 1: View factors TR 17603-31-01 Part 2 Thermal design handbook – Part 2: Holes, Grooves and Cavities TR 17603-31-01 Part 3 Thermal design handbook – Part 3: Spacecraft Surface Temperature TR 17603-31-01 Part 4 Thermal design handbook – Part 4: Conductive Heat Transfer TR 17603-31-01 Part 5 Thermal design handbook – Part 5: Structural Materials: Metallic and Composite TR 17603-31-01 Part 6 Thermal design handbook – Part 6: Thermal Control Surfaces TR 17603-31-01 Part 7 Thermal design handbook – Part 7: Insulations TR 17603-31-01 Part 8 Thermal design handbook – Part 8: Heat Pipes TR 17603-31-01 Part 9 Thermal design handbook – Part 9: Radiators TR 17603-31-01 Part 10 Thermal design handbook – Part 10: Phase – Change Capacitors TR 17603-31-01 Part 11 Thermal design handbook – Part 11: Electrical Heating TR 17603-31-01 Part 12 Thermal design handbook – Part 12: Louvers TR 17603-31-01 Part 13 Thermal design handbook – Part 13: Fluid Loops TR 17603-31-01 Part 14 Thermal design handbook – Part 14: Cryogenic Cooling TR 17603-31-01 Part 15 Thermal design handbook – Part 15: Existing Satellites TR 17603-31-01 Part 16 Thermal design handbook – Part 16: Thermal Protection System

Solid-liquid phase-change materials (PCM) are a favoured approach to spacecraft passive thermal control for incident orbital heat fluxes or when there are wide fluctuations in onboard equipment. The PCM thermal control system consists of a container which is filled with a substance capable of undergoing a phase-change. When there is an the increase in surface temperature of spacecraft the PCM absorbs the excess heat by melting. If there is a temperature decrease, then the PCM can provide heat by solidifying. Many types of PCM systems are used in spacecrafts for different types of thermal transfer control. Characteristics and performance of phase control materials are described in this Part. Existing PCM systems are also described. The Thermal design handbook is published in 16 Parts TR 17603-31-01 Part 1 Thermal design handbook – Part 1: View factors TR 17603-31-01 Part 2 Thermal design handbook – Part 2: Holes, Grooves and Cavities TR 17603-31-01 Part 3 Thermal design handbook – Part 3: Spacecraft Surface Temperature TR 17603-31-01 Part 4 Thermal design handbook – Part 4: Conductive Heat Transfer TR 17603-31-01 Part 5 Thermal design handbook – Part 5: Structural Materials: Metallic and Composite TR 17603-31-01 Part 6 Thermal design handbook – Part 6: Thermal Control Surfaces TR 17603-31-01 Part 7 Thermal design handbook – Part 7: Insulations TR 17603-31-01 Part 8 Thermal design handbook – Part 8: Heat Pipes TR 17603-31-01 Part 9 Thermal design handbook – Part 9: Radiators TR 17603-31-01 Part 10 Thermal design handbook – Part 10: Phase – Change Capacitors TR 17603-31-01 Part 11 Thermal design handbook – Part 11: Electrical Heating TR 17603-31-01 Part 12 Thermal design handbook – Part 12: Louvers TR 17603-31-01 Part 13 Thermal design handbook – Part 13: Fluid Loops TR 17603-31-01 Part 14 Thermal design handbook – Part 14: Cryogenic Cooling TR 17603-31-01 Part 15 Thermal design handbook – Part 15: Existing Satellites TR 17603-31-01 Part 16 Thermal design handbook – Part 16: Thermal Protection System

CEN/CLC/TR 17603-31-10:2021 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 49.140 - Space systems and operations. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

CEN/CLC/TR 17603-31-10:2021 has the following relationships with other standards: It is inter standard links to EN ISO 8528-10:2022. Understanding these relationships helps ensure you are using the most current and applicable version of the standard.

CEN/CLC/TR 17603-31-10:2021 is associated with the following European legislation: Standardization Mandates: M/496. When a standard is cited in the Official Journal of the European Union, products manufactured in conformity with it benefit from a presumption of conformity with the essential requirements of the corresponding EU directive or regulation.

CEN/CLC/TR 17603-31-10:2021 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

SLOVENSKI STANDARD

01-oktober-2021

Vesoljska tehnika - Priročnik o toplotni zasnovi - 10. del: Kondenzatorji s faznimi

prehodi

Space engineering - Thermal design handbook - Part 10: Phase - Change Capacitor

Raumfahrttechnik - Handbuch für thermisches Design - Teil 10: Kondensatoren mit

Phasenübergängen

Ingénierie spatiale - Manuel de conception thermique - Partie 10: Réservoirs de

matériaux à changement de phase

Ta slovenski standard je istoveten z: CEN/CLC/TR 17603-31-10:2021

ICS:

31.060.99 Drugi kondenzatorji Other capacitors

49.140 Vesoljski sistemi in operacije Space systems and

operations

2003-01.Slovenski inštitut za standardizacijo. Razmnoževanje celote ali delov tega standarda ni dovoljeno.

TECHNICAL REPORT

CEN/CLC/TR 17603-31-

RAPPORT TECHNIQUE

TECHNISCHER BERICHT

August 2021

ICS 49.140

English version

Space engineering - Thermal design handbook - Part 10:

Phase - Change Capacitor

Ingénierie spatiale - Manuel de conception thermique - Raumfahrttechnik - Handbuch für thermisches Design -

Partie 10 : Réservoirs de matériaux à changement de Teil 10: Kondensatoren mit Phasenübergängen

phase

This Technical Report was approved by CEN on 21 June 2021. It has been drawn up by the Technical Committee CEN/CLC/JTC 5.

CEN and CENELEC members are the national standards bodies and national electrotechnical committees of Austria, Belgium,

Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy,

Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Republic of North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia,

Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and United Kingdom.

CEN-CENELEC Management Centre:

Rue de la Science 23, B-1040 Brussels

© 2021 CEN/CENELEC All rights of exploitation in any form and by any means Ref. No. CEN/CLC/TR 17603-31-10:2021 E

reserved worldwide for CEN national Members and for

CENELEC Members.

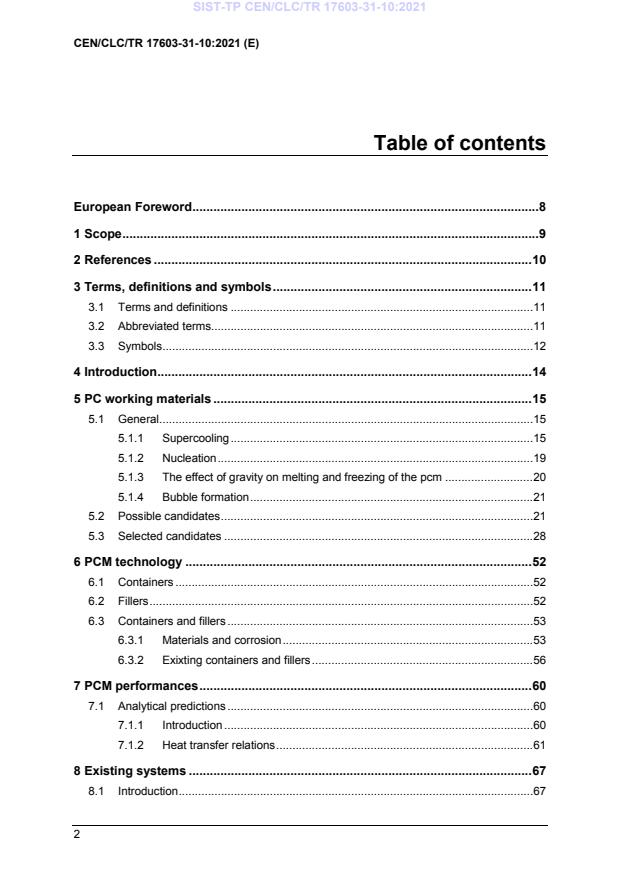

Table of contents

European Foreword . 8

1 Scope . 9

2 References . 10

3 Terms, definitions and symbols . 11

3.1 Terms and definitions . 11

3.2 Abbreviated terms. 11

3.3 Symbols . 12

4 Introduction . 14

5 PC working materials . 15

5.1 General . 15

5.1.1 Supercooling . 15

5.1.2 Nucleation . 19

5.1.3 The effect of gravity on melting and freezing of the pcm . 20

5.1.4 Bubble formation . 21

5.2 Possible candidates . 21

5.3 Selected candidates . 28

6 PCM technology . 52

6.1 Containers . 52

6.2 Fillers . 52

6.3 Containers and fillers . 53

6.3.1 Materials and corrosion . 53

6.3.2 Exixting containers and fillers . 56

7 PCM performances . 60

7.1 Analytical predictions . 60

7.1.1 Introduction . 60

7.1.2 Heat transfer relations . 61

8 Existing systems . 67

8.1 Introduction . 67

8.2 Dornier system . 68

8.3 Ike . 81

8.4 B&k engineering . 101

8.5 Aerojet electrosystems . 106

8.6 Trans temp . 116

Bibliography . 126

Figures

Figure 5-1: Temperature, T, vs. time, t, curves for heating and cooling of several PCMs.

From DORNIER SYSTEM (1971) [9]. . 18

Figure 5-2: Temperature, T, vs. time, t, curves for heating and cooling of several PCMs.

From DORNIER SYSTEM (1971) [9]. . 19

Figure 5-3: Density, ρ, vs. temperature T, for several PCMs. From DORNIER System

(1971) [9]. . 47

Figure 5-4: Specific heat, c, vs. temperature T, for several PCMs. From DORNIER

System (1971) [9]. . 48

Figure 5-5: Thermal conductivity, k, vs. temperature T, for several PCMs. From

DORNIER System (1971) [9]. . 49

Figure 5-6: Vapor pressure, p , vs. temperature T, for several PCMs. From DORNIER

v

System (1971) [9]. . 50

Figure 5-7: Viscosity, µ, vs. temperature T, for several PCMs. From DORNIER System

(1971) [9]. . 51

Figure 5-8: Isothermal compressibility, χ, vs. temperature T, for several PCMs. From

DORNIER System (1971) [9]. . 51

Figure 6-1: Container with machined wall profile and welded top and bottom.

Honeycomb filler with heat conduction fins. All the dimensions are in mm.

From DORNIER SYSTEM (1972) [10]. . 57

Figure 6-2: Fully machined container with welded top. Honeycomb filler. All the

dimensions are in mm. From DORNIER SYSTEM (1972) [10]. . 58

Figure 6-3: Machined wall container profile with top and bottom adhesive bonded.

Alternative filler types are honeycomb or honeycomb plus fins. All the

dimensions are in mm. From DORNIER SYSTEM (1972) [10]. . 59

Figure 7-1: Sketch of the PCM package showing the solid-liquid interface. . 61

Figure 7-2: PCM mass, M , filler mass, M , package thickness, L, temperature

PCM F

excursion, ∆T, and total conductivity, k , as functions of the ratio of filler

T

area to total area, A /A . Calculated by the compiler. . 65

F T

Figure 7-3: PCM mass, M , filler mass, M , package thickness, L, temperature

PCM F

excursion, ∆T, and total conductivity, k , as functions of the ratio of filler

T

area to total area, A /A . Calculated by the compiler. . 66

F T

Figure 8-1: PCM capacitor for eclipse temperature control developed by Dornier

System. . 71

Figure 8-2: 30 W.h PCM capacitors developed by Dornier System. a) Complete PCM

capacitor. b) Container and honeycomb filler with cells normal to the heat

input/output face. c) Container, honeycomb filler with cells parallel to the

heat input/output face, and cover sheets. . 71

Figure 8-3: PCM mounting panels developed by Dornier Syatem. b) Shows the

arrangement used for thermal control of four different heat sources. . 72

Figure 8-4: Thermal control system formed by, from right to left, a: PCM capacitor, b:

axial heat pipe and, c: flat plate heat pipe. This system was developed by

Dornier System for the GfW-Heat Pipe Experiment. October 1974. . 76

Figure 8-5: PCM capacitor shown in the above figure. 76

Figure 8-6: Temperature, T, as selected points in the complete system vs. time, t,

during heat up. a) Ground tests. Symmetry axis in horizontal position. Q =

28 W. b) Ground tests. Symmetry axis in vertical position. Q = 28 W. The

high temperatures which appear at start-up are due to pool boiling in the

evaporator of the axial heat pipe. c) Flight experiment under microgravity

conditions. Q not given. notice time scale. . 77

Figure 8-7: PCM capacitor developed by Dornier System for temperature control of two

rate gyros onboard the Sounding Rocket ESRO "S-93". . 79

Figure 8-8: Test model of the above PCM capacitor. In the figure are shown, from right

to left, the two rate gyros, the filler and the container. 79

Figure 8-9: Temperature, T, at the surface of the rate gyros, vs. time, t . Ambient

temperature, T = 273 K. Ambient temperature, T = 273 K.

R R

Ambient temperature changing between 273 K and 333 K. This

curve shows the history of the ambient temperature used as input for the

last curve above. References: DORNIER SYSTEM (1972) [10], Striimatter

(1972) [22]. . 80

Figure 8-10: Location of the thermocouples in the input/output face. The thermocouples

placed on the opposite face do not appear in the figure since they are

projected in the same positions as those in the input/output face. All the

dimensions are in mm. . 83

Figure 8-11: Prototype PCM capacitor developed by IKE. All the dimensions are in mm.

a: Box. b: Honeycomb half layer. c: Perforations in compartment walls. d:

pinch tube. e: Extension of the pinch tube. . 85

Figure 8-12: Time, t, for nominal heat storage and temperature, T of the heat transfer

face vs. heat input rate, Q . Time for nominal heat storage. Measured

average wall temperature at time t . Measured temperature at the center

of the heat transfer face at time t. . 86

Figure 8-13: Time, t , for complete melting and temperature, T, of the heat transfer

max

face vs. heat input rate, Q. Time for complete melting: measured.

calculated by model A. Calculated by models B or C. Average wall

temperature at time t : measured. calculated by model A.

max

Calculated by models B or C. Measured temperature at the center of the

heat transfer face at t . . 86

max

Figure 8-14: Location of the thermocouples in the heat input/output face (f) and within

the box (b). The thermocouples placed on the opposite face do not appear

in the figure since they are projected on the same positions as those in the

input/output face. All the dimensions are in mm. . 89

Figure 8-15: PCM capacitors with several fillers developed by IKE. All the dimensions

are in mm. a: Model 1. b: Model 2. c: Model 3. d: Model 4. . 91

Figure 8-16: Measured temperature, T, at several points of the PCM capacitor vs. time

t. Model 2. Heat up with a heat transfer rate Q = 30,6 W. Points are placed

as follows (Figure 8-14): Upper left corner of the heat input/output

face. Center of the insulated face. Center of the box,

immersed in the PCM. Time for complete melting t , is shown by means

max

of a vertical trace intersecting the curves. 92

Figure 8-17: Time for complete melting, tmax, vs. heat input rate Q . Model 1.

Measured. Model 2. Measured. Calculated by using model A.

Model 3. Measured. Calculated by using model A.

Calculated by using model B. Model 4. Measured. . 92

Figure 8-18: Largest measured temperature, T, of the heat input/output face vs. heat

input rate, Q .Model 1. Measured. Model 2. Measured.

Calculated by using model A. Model 3. Measured. Calculated by

using model A. Calculated by using model B. Model 4. Measured. . 93

Figure 8-19: Location of the thermocouples in the heat input/output face. The

thermocouples placed on the opposite face do not appear in the figure

since they are projected on the same positions as those in the input/output

face. Thermocouples are numbered for later reference. All the dimensions

are in mm. . 96

Figure 8-20: PCM capacitor developed by IKE for ESA (ESTEC). All the dimensions

are in mm. a: Box. b: Honeycomb calls. c: Perforations in compartment

walls. d: Pinch tube. . 98

Figure 8-21: Measured temperature, T at several points in either of the large faces of

the container vs. time, t. Heat up with a heat transfer rate Q = 86,4 W.

Points 1 to 5 are placed in the heat input/output face as indicated in Figure

8-19. Circled points are in the same positions at the insulated face. Time for

complete melting, t , is shown by means of a vertical trace intersecting

max

the curves. . 99

Figure 8-22: Time for complete melting, t vs. heat input rate, Q . Measured.

max

Calculated by using the 26 nodes model. Overall thermal conductances in

−1 −1

the range 1,4 W.K to 5,6 W.K . . 99

Figure 8-23: Average temperature, T of either of the large faces vs. heat input rate, Q. t

= t . Heat input/output face. Measured. Calculated by the 26

max

− 1

nodes model. Overall thermal conductance 5,6 W.K . Calculated

−1

as above. Overall thermal conductance 6,7 W.K . Insulated face.

Measured. Calculated as above. Overall thermal conductance 5,6

−1 −1

W.K and 6,7 W.K . . 100

Figure 8-24: Set-up used for component tests. . 103

Figure 8-25: PCM capacitor developed by B & K Engineering for NASA. All the

dimensions are in mm. . 104

Figure 8-26: Schematic of the PCM capacitor in the TIROS-N cryogenic heat pipe

experiment package (HEPP). From Ollendorf (1976) [20]. . 104

Figure 8-27: Average temperature, T of the container vs. time, t , during heat up for two

different heat transfer rates. Q = 25 W. Q = 45 W. Component tests

data. . 105

Figure 8-28: Average temperature, T, of the container vs. time, t, during cool down.

Data from either component or system tests. Component tests, Q = 6,1

W. Freezing interval ∆t≅ 4,5 h. System tests, Q = 5,2 W. Freezing

interval ∆t≅ 5 h. Time for complete melting, tmax, is shown by means of a

vertical trace intersecting the curves. . 105

Figure 8-29: Set up used for the “Beaker” tests. . 108

Figure 8-30: Set up used for the "Canteen" tests. Strain gage.

Temperature sensor. . 109

Figure 8-31: PCM capacitor developed by Aerojet ElectroSystems Company. The outer

diameter is given in mm. . 109

Figure 8-32: "Canteen" simulation of the S day. a) Heat transfer rate, Q vs. time, t. b)

PCM temperature, T, vs. time t. Data in the insert table estimated by the

compiler through area integration and the value of h in Tables 8-9 and 8-

f

10. . 110

Figure 8-33: Maximum diurnal temperature, T of the radiator vs. orbital time, t.

Predicted with no-phase change. Measured. Phase-change attenuated

the warming trend of the radiator for eleven months (performance

extension). . 110

Figure 8-34: Location of the thermocouples and strain gages in the test unit.

Thermocouples 12, 17 and 14 are placed on the base; 6, 7 and 8 on the

upper face; 9 and 10 on the lateral faces; 11 on the rim, and 26 on the

mounting hub interface. Strain gages are placed on his upper face. 114

Figure 8-35: PCM capacitor developed by Aerojet. All the dimensions are in mm. . 114

Figure 8-36: Average temperature, T, of the container vs. time, t, either during heat up

or during cool down. a) During heat up with a nominal heat transfer rate Q =

2,5 W. b) During cool down with the same nominal heat transfer rate. With

honeycomb filler. Mounting hub down. Measured. Calculated.

Cooling coils down. Measured. Calculated. Without honeycomb

filler. Cooling coils up. Measured. Calculated with the original

model. Calculated with the modified model. Cooling coils down.

Measured. Times for 90% and complete melting (freezing) are shown in the

figure by means of vertical traces intersecting the calculated curves.

Replotted by the compiler, after Bledjian, Burden & Hanna (1979) [6], by

shifting the time scale in order to unify the initial temperatures. . 115

Figure 8-37: Several TRANS TEMP Containers developed by Royal Industries for

transportation of temperature- sensitive products. a: 205 System. b: 301

System. c: 310 System. 1: Outer insulation. 2: PCM container. . 125

Figure 8-38: Measured ambient and inner temperatures, T vs. time, t, for several

TRANS TEMP Containers holding blood samples. a: 205 System. b: 301

System. c: 310 System. Ambient temperature. Inner

temperature. . 125

Tables

Table 5-1: Supercooling Tests . 17

Table 5-2: PARAFFINS . 22

a

Table 5-3: NON-PARAFFIN ORGANICS . 23

Table 5-4: SALT HYDRATES . 24

Table 5-5: METALLIC . 26

Table 5-6: FUSED SALT EUTECTICS . 27

Table 5-7: MISCELLANEOUS . 27

Table 5-8: SOLID-SOLID . 28

Table 5-9: PARAFFINS . 29

Table 5-10: PARAFFINS . 30

Table 5-11: PARAFFINS . 32

Table 5-12: NON-PARAFFIN ORGANICS . 34

Table 5-13: NON-PARAFFIN ORGANICS . 35

Table 5-14: NON-PARAFFIN ORGANICS . 37

Table 5-15: NON-PARAFFIN ORGANICS . 39

Table 5-16: NON-PARAFFIN ORGANICS . 40

Table 5-17: SALT HYDRATES . 42

Table 5-18: METALLIC AND MISCELLANEOUS . 45

Table 6-1: Physical Properties of Several Container and Filler Materials . 54

Table 6-2: Compatibility of PCM with Several Container and Filler Materials . 55

European Foreword

This document (CEN/CLC/TR 17603-31-10:2021) has been prepared by Technical Committee

CEN/CLC/JTC 5 “Space”, the secretariat of which is held by DIN.

It is highlighted that this technical report does not contain any requirement but only collection of data

or descriptions and guidelines about how to organize and perform the work in support of EN 16603-

31.

This Technical report (TR 17603-31-10:2021) originates from ECSS-E-HB-31-01 Part 10A.

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. CEN [and/or CENELEC] shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such

patent rights.

This document has been prepared under a mandate given to CEN by the European Commission and

the European Free Trade Association.

This document has been developed to cover specifically space systems and has therefore precedence

over any TR covering the same scope but with a wider domain of applicability (e.g.: aerospace).

Scope

Solid-liquid phase-change materials (PCM) are a favoured approach to spacecraft passive thermal

control for incident orbital heat fluxes or when there are wide fluctuations in onboard equipment.

The PCM thermal control system consists of a container which is filled with a substance capable of

undergoing a phase-change. When there is an the increase in surface temperature of spacecraft the

PCM absorbs the excess heat by melting. If there is a temperature decrease, then the PCM can provide

heat by solidifying.

Many types of PCM systems are used in spacecrafts for different types of thermal transfer control.

Characteristics and performance of phase control materials are described in this Part. Existing PCM

systems are also described.

The Thermal design handbook is published in 16 Parts

TR 17603-31-01 Thermal design handbook – Part 1: View factors

TR 17603-31-02 Thermal design handbook – Part 2: Holes, Grooves and Cavities

TR 17603-31-03 Thermal design handbook – Part 3: Spacecraft Surface Temperature

TR 17603-31-04 Thermal design handbook – Part 4: Conductive Heat Transfer

TR 17603-31-05 Thermal design handbook – Part 5: Structural Materials: Metallic and

Composite

TR 17603-31-06 Thermal design handbook – Part 6: Thermal Control Surfaces

TR 17603-31-07 Thermal design handbook – Part 7: Insulations

TR 17603-31-08 Thermal design handbook – Part 8: Heat Pipes

TR 17603-31-09 Thermal design handbook – Part 9: Radiators

TR 17603-31-10 Thermal design handbook – Part 10: Phase – Change Capacitors

TR 17603-31-11 Thermal design handbook – Part 11: Electrical Heating

TR 17603-31-12 Thermal design handbook – Part 12: Louvers

TR 17603-31-13 Thermal design handbook – Part 13: Fluid Loops

TR 17603-31-14 Thermal design handbook – Part 14: Cryogenic Cooling

TR 17603-31-15 Thermal design handbook – Part 15: Existing Satellites

TR 17603-31-16 Thermal design handbook – Part 16: Thermal Protection System

References

EN Reference Reference in text Title

EN 16601-00-01 ECSS-S-ST-00-01 ECSS System - Glossary of terms

TR 17603-30-06 ECSS-E-HB-31-01 Part 6 Thermal design handbook – Part 6: Thermal

Control Surfaces

TR 17603-30-11 ECSS-E-HB-31-01 Part 11 Thermal design handbook – Part 11: Electrical

Heating

All other references made to publications in this Part are listed, alphabetically, in the Bibliography.

Terms, definitions and symbols

3.1 Terms and definitions

For the purpose of this Standard, the terms and definitions given in ECSS-S-ST-00-01 apply.

3.2 Abbreviated terms

The following abbreviated terms are defined and used within this Standard.

air traffic control (aerosat)

ATC

Brennan & Kroliczek

B & K

Gessellschaft für Weltraumforschung

GfW

heat pipe experiment package

HEPP

HLS

international heat pipe experiment

IHPE

institut für kernenenergetik (university of Stuttgart)

IKE

long duration exposure facility

LDEF

methyl-ethyl ketone

MEK

multilayer insulation

MLI

phase-change material

PCM

systems improved numerical differencing analyzer

SINDA

stainless steel

SS

second surface mirror

SSM

stoichiometric day, see clause 8.5

S day

tungsten-inert gas

TIG

television and infra-red observation satellite

TIROS

tag open cup

TOC

tag closed cup

TCC

transporter heat pipe

TPHP

Other Symbols, mainly used to define the geometry of the configuration, are introduced when

required.

3.3 Symbols

cross-sectional area, [m ]

A

modulus of elasticity, [Pa]

E

maximum energy stored in the PCM device, [J]

Emax

thickness of the PCM device, one-dimensional model,

L

[m]

mass, [kg]

M

heat transfer rate, [W]

Q

temperature, [K]

T

melting (or freezing) temperature, [K]

TM

temperature of the components being controlled, [K]

T0

reference temperature, [K]

TR

excursion temperature, [K], ∆T = T0−TM

∆T

− −

1 1

specific heat, [J.kg .K ]

c

−

heat of fusion, [J.kg ]

hf

−

heat of transition, [J.kg ]

ht

− −

1 1

thermal conductivity, [W.m .K ]

k

vapor pressure, [Pa]

pv

heat flux to the PCM device, one-dimensional model,

q0

−

[W.m ]

heat flux from the PCM device to the heat sink, one-

qR

−

dimensional model, [W.m ]

interface position, measured from x = 0, one-

s(t)

dimensional model, [m]

time, [d], [h], [min], [s]

t

time for complete melting, [h]

tmax

time for melting 90% of the volume of the PCM, [h]

t90

geometrical coordinate, one-dimensional model, [m]

x

−

2 1

thermal diffusivity, [m .s ], α = k/ρc

α

thermal expansion coefficient, volumetric (unless

β

−

otherwise stated), [K ]

µ dynamic viscosity, [Pa.s]

−

ρ density, [kg.m ]

−

surface tension, [N.m ]

σ

ultimate tensile strength, [pa]

σult

−

χ isothermal compressibility, [Pa ]

Subscripts

Container

C

Filler

F

Phase-Change Material

PCM

Total

T

Liquid

l

Solid

s

Introduction

Solid-liquid phase-change materials (PCM) present an attractive approach to spacecraft passive

thermal control when the incident orbital heat fluxes or the onboard equipment heat dissipation

fluctuate widely.

Basically the PCM thermal control system consists of a container which is filled with a substance

capable of undergoing a phase-change. When the temperature of the spacecraft surface increases,

either because external radiation or inner heat dissipation, the PCM will absorb the excess heat

through melting, and will restore it through solidification when the temperature decreases again.

Because of the obvious electrical analogy this thermal control system is also called PCM capacitor.

To control the temperature of a cyclically operating equipment, the PCM cell is normally sandwiched

between the equipment and the heat sink.

When the PCM system aims at absorbing the abnormal heat dissipation peaks of an equipment which

somehow the excess heat to a sink, the cell is placed in contact with the equipment, without interfering

in the normal heat patch between equipment and heat sink.

For achieving the thermal control of solitary equipment, the PCM capacitor may be used as the sole

heat sink, provided that the heat transferred during the heating period does not exceed that required

to completely melt the material.

PC working materials

5.1 General

The ideal PCM would have the following characteristics:

1. Melting point within the allowed temperature range of the thermally controlled

component. In general between 260 K and 315 K.

2. High heat of fusion. This property defines the available energy storage and may be

important either on a mass basis or on a volume basis.

3. Reversible solid-to-liquid transition. The chemical composition of the solid and liquid

phases should be the same.

4. High thermal conductivity. This property is necessary to reduce thermal gradients.

Unfortunately most PCM are very poor thermal conductors, so that fillers are used to

increase the conductivity of the system.

5. High specific heat and high density.

6. Long term reliability during repeated cycling.

7. Low volume change during phase transition.

8. Low vapor pressure.

9. Non-toxic.

10. Non-corrosive. Compatible with structural materials.

11. No tendency to supercooling.

12. Availability and reasonable cost.

Relevant physical characteristics of phase-changing system are discussed, from a general point of

view, in the following pages.

5.1.1 Supercooling

Supercooling is the process of cooling a liquid below the solid-liquid equilibrium temperature without

formation of the solid phase. Supercooling when only one phase is present is called one-phase

supercooling. Supercooling in the presence of both solid and liquid, or two-phase supercooling,

depends upon the particular material and the environment surrounding it. The best way to reduce

supercooling is to ensure that the original crystalline material has not been completely molten In such

a case the seeds which are present in the melt tend to nucleate the solid phase when heat is removed.

Nucleating catalysts are available for many materials.

Several PCMs have been tested under repeated heating and freezing cycles by DONIER SYSTEM. The

main purpose of these tests has been the detection of eventual supercooling phenomena. Among the

tested materials, the normal paraffins did not show any supercooling tendency. This result is also

confirmed by the available literature. However, according to investigations carried out by Bentilla,

Sterrett & Karre (1966) [5], contamination of the paraffins with water leads to supercooling of the

molten substance down to 283 K. Care should therefore be taken to prevent this contamination.

5.1.1.1 Experimental investigations

An experimental investigation has been performed by DORNIER SYSTEM with the aim of finding out

the variables having any influence on the supercooling behavior of the PCM; namely: total number of

cycles, cooling rate, and type of container.

In these experiments, the temperature of the test chamber was alternatively increased and decreased

at constant steps within a range of 240 to 320 K. The results are summarized in Table 5-1, and Figure

5-1 and Figure 5-2.

The temperature history of both the PCM inside the containers and the honey comb packages was

measured by means of copper-constant thermocouples, and continuously recorded. The test points

were located in the center of the container.

5.1.1.2 Results

Water and paraffins did not show any tendency to supercooling during freezing, not even at the

− −

2 1

maximum realizable cooling rate of 2x10 K.s .

Acetic acid showed supercooling of different orders of magnitude. It could not be determined whether

or not supercooling is a function of cooling rate. Supercooling was also independent, at least not

noticeably dependent, on the number of cells constituting the container. If however, Al-chips were

added to facilitate heterogeneous nucleation, supercooling was reduced during the first cycles,

although it augmented when the test time increased.

Supercooling of disodium hydroxide heptahydrate amounted to 3-3,5 K regardless of cooling rate and

number of temperature cycles.

Table 5-1: Supercooling Tests

PCM Container Number of FIRST CYCLE Maximum Comments

Cycles Supercooling

Plateau Temperature [K] Supercooling

DODECANE Aluminium Cell. 146 265 NO NO

Honeycomb adhesive-

bonded to end plate.

TETRADECANE Aluminium Cell. 50 280 NO NO Slightly ascending

Honeycomb adhesive- temperature.

bonded to end plate.

HEXADECANE Test tube without 50 293 NO NO

honeycomb.

Aluminium Cell. 70 300 ∆T =9,5 K ∆T = 10 K

Honeycomb adhesive-

bonded to end plate.

ACETIC ACID Neck flash with splinters. 70 301 NO ∆T = 6,5 K Normal supercooling:

∆T= 5 K

Aluminium Cell. 23 299 ∆T = 1,5 K ∆T = 5 K

Honeycomb inserted (not

adhered).

DISODIUM Neck flash with splinters. 36 286,5 ∆T = 3,5 K ∆T = 3,5 K No plateau

HYDROXIDE temperature during

22 287 ∆T = 2,5 K ∆T = 3 K

HEPTAHYDRATE heating-up.

DISTILLED WATER Aluminium Cell. 85 274 NO NO

Honeycomb adhesive-

bonded to end plate.

NOTE From DORNIER SYSTEM (1971) [9].

Figure 5-1: Temperature, T, vs. time, t, curves for heating and cooling of several

PCMs. From DORNIER SYSTEM (1971) [9].

Figure 5-2: Temperature, T, vs. time, t, curves for heating and cooling of several

PCMs. From DORNIER SYSTEM (1971) [9].

5.1.2 Nucleation

Nucleation is the formation of the first crystals capable of spontaneous growth into large crystals in an

unstable liquid phase. These first crystals are called nuclei.

Homogeneous nucleation occurs when the nuclei may be generated spontaneously from the liquid

itself at the onset of freezing. The rates of formation and dissociation do not depend on the presence or

absence of surfaces, such as container walls or foreign particles.

Heterogeneous nucleation occurs when the nuclei are formed on solid particles already in the system

or at the container walls. Supercooling (see clause 5.1.1) can be considerably reduced or even

eliminated when heterogeneous nucleation is present.

5.1.3 The effect of gravity on melting and freezing of the pcm

Gravitational forces between molecules are comparatively small relative to intermolecular or

interatomic forces; for example, the ratio between gravitational and intermolecular forces between two

−

molecules of carbon dioxide is of the order of 10 .

Since phase-change is controlled by intermolecular forces, the rate of melting or freezing should be the

same under microgravity as it is under normal gravity conditions, provided that thermal and solutal

fields are the same.

However, phase change happens to be indirectly influenced by gravity through the following effects:

1. Convection in the liquid phase which propagates nuclei and enhances heat transfer, and

2. thermal contact conductance between the heated (or cooled) wall and the PCM.

1. Convection can be induced by volume forces and/or by surface forces.

When the density gradient (due to thermal, solutal, or other effects) is not aligned with

the body force (gravitational) vector, flow immediately results no matter how small the

gradient. On the other hand, when the density gradient is parallel to but opposed to the

body force, the fluid remains in a state of unstable equilibrium until a critical density

gradient (more precisely, a critical Grashof number) is exceeded. The Grashof number

gives the ratio of buoyancy to viscous forces.

Convection from the interfaces is produced by surface tractions due to surface tension

gradients (which again can be due to thermal, solutal, or other effects). If the temperature

gradient is parallel to the undisturbed interface, flow immediately results no matter how

small the gradient. When the temperature gradient is normal to the undisturbed

interface, convection appears provided that a critical Marangoni number is exceeded.

This Marangoni number is defined as the ratio of surface tension gradient forces to

viscous forces.

A priori information on which type of convection prevails under given circumstances can

be obtained from an order of magnitude analysis (Napolitano (1981) [19]). Nevertheless,

convection is presumably negligible for most PCM capacitors because of the low

temperature gradients (associated to the high thermal conductances usually required)

and of the reduced characteristics lengths of the enclosures when a metallic filler is used (

see clause 6.2).

Convection due to shrinkage forces associated to phase change is normally small when

solid and liquid densities are not too different.

2. Gravity presses the denser phase against the lower wall of the container.

At the onset of the cool down the liquid remains in contact with the lower wall, be it

cooled or heated, while the upper part of the cell is empty because of the void (ullage)

which is usually provided for safe operation at high temperatures when using rigid

containers (see clause 6.1). Thence, the temperature of the cooled wall is expected to be

lower when the device is cooled from above (poor thermal conductance), that when

cooled from below.

As soon as the cool down progresses, the solid, which is assumed to be denser than the

liquid, makes contact with the lower wall enhancing the heat transfer to it, because the

solid phase has normally a higher thermal conductivity than the liquid.

Reliable cooling data of PCM cells are not easily found in the literature since cooling is

difficult to control precisely. Data reported in Figure 8-36b, Clause 8.5, do not support the

above prediction, rather the average wall temperature is higher (not smaller) when the

solid is pressed by gravity against the cooled wall. Notice, however that according to

Table 5-9, clause 5.3, liquid 1-Heptene is more conductive than the solid.

During heat up, the insulation is similar. Since the frozen PCM is usually denser than the

liquid, the solid falls to the bottom of the cell. When heating up from below, the solid

PCM remains close to the heated face, with a thin liquid layer amid them, whereas when

heated from above a void space or, at most, a thick gap filled with the liquid appears

between the heated face and the solid PCM. Thence, the heated wall temperature is

expected to be higher when the device is heated from above than when it is heated from

below. This effect has been observed experimentally, see for instance, in clause 8.3 the

tests corresponding to Figure 8-14. Melting time is barely affected by the orientation of

the gravity vector.

Metallic fillers (see clause 6.2) have the two-fold effect of increasing the thermal contact

conductance between container and PCM, and of impeding liquid motion. Migration of

the liquid by capillary pumping toward selected parts of the container can be achieved by

varying the cross sectional area of the filler cells as in the PCM device shown in clause

8.4.

5.1.4 Bubble formation

Bubbles can affect PCM operation in several ways: the thermal conductivity will be altered; bubbles in

the liquid phase will cause stirring actions; small bubbles in the solid phase can take up some of the

volume shrinkage, thereby avoiding the formation of large cavities.

There are several types of bubbles likely to occur during PCM performance under microgravity: PCM

vapor bubbles, cavities or voids from volume shrinkage, and gas bubbles.

The most persistent bubbles seem to be those formed by dissolved gases. During solidification,

dissolved gases can be rejected just as any other solute at the solid-liquid interface. During the reverse

process of melting, bubbles previously overgrown in the solid can be liberated. In an one-g field,

bubbles would be more likely to float to the top and coalesce. Under microgravity, bubbles would be

trapped in the frozen solid.

In order to reduce the amount of dissolved gases it is suggested to boil the PCM in liquid form under

reduced p

...

Questions, Comments and Discussion

Ask us and Technical Secretary will try to provide an answer. You can facilitate discussion about the standard in here.

Loading comments...